We should include not just individuals but corp's, by the way.

To say that "ultimately the public will decide" is something like a parent telling a child "everything will be all right," when in fact the parent has no basis for that prediction.Įxtreme concentration of wealth/power is both symptom and cause. writing for the majority) shake that confidence because they entrench the power of the plutocracy. Archer & White Sales, 2019, Kavanaugh, J. Supreme Court decisions like Citizens United and the string of decisions upholding arbitration agreements even on the question of determining the enforceability of arbitration agreements (Schein v. But that was half a century ago: my confidence came in large part from a childhood and young adulthood under the wings of the Warren and even Burger Courts. I used to feel great confidence in the American system, based on the fact that it was able to end the influence of people like Joe McCarthy and Richard Nixon. Something troubles me about this last sentence: how can we be so confident that "the public" will decide the fate of the public sphere when the public sphere is dominated by plutocrats? Not just the Murdochs and Bezoses who fund conventional media, but also those who control social networks and resist attempts to eliminate the bots that are deliberately trying to tilt public opinion. and worse hijacked to misinform the general public in all sorts of dangerous ways. The potential to use modern technology for good has been hijacked by merely using it for maximizing profit. I see all encompassing socio-enviro-economic dysfunction enabled by the injustice of modern rule of law and all sorts of political and economic mythology that has little connection with factual reality.

WELCOME TO PLUTOCRACY HOW TO

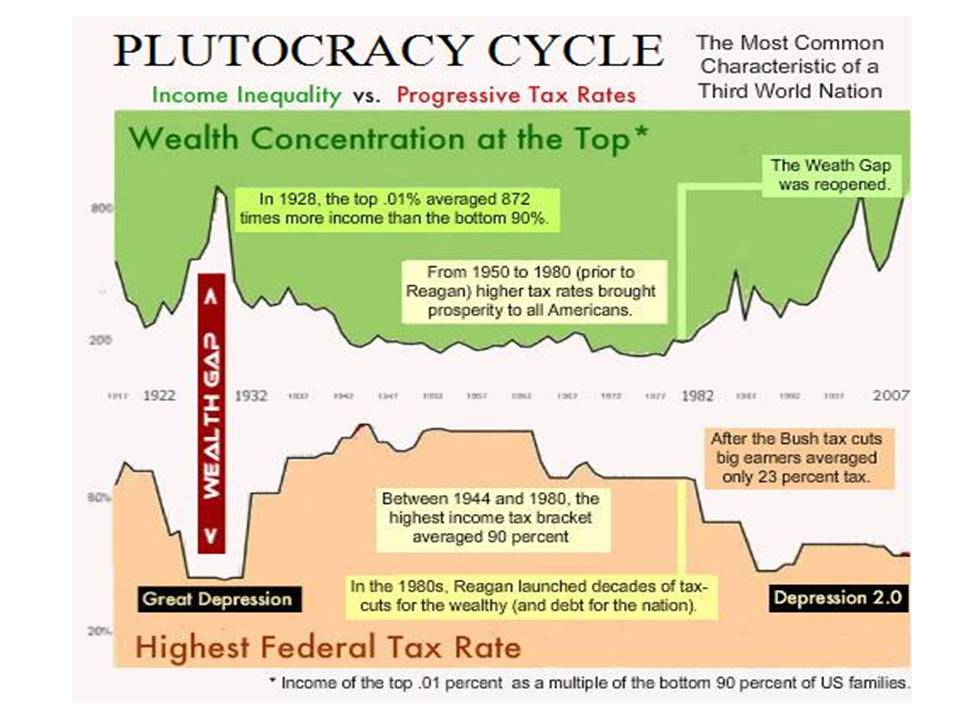

I don't see any recent leaders who have much of a grasp on how to address this problem. A very large number of families in GDP rich countries are struggling to pay their bills every month, and this has been getting worse year after year for the best part of 50 years. There is a massive chasm between the dialog in academia and the corridors of power and the everyday conversation around the kitchen table. My take on the last 50+ years is that we have failed to understand the behavior of knowledge, that is the interaction between individual people and a massive amount of available knowledge. I graduated from Cambridge in 1961 after studying engineering and economics. “While vigilance can mitigate the extent to which the wealthy get to define the policy agenda,” he writes, “in the end big money will find a way – unless there’s less big money to begin with.” Hence, curbing plutocracy should be America’s top priority. Would the US economy of the 2010s have been materially different if the share of total income accruing to the top 0.01% had not quadrupled in recent decades, from 1.3% to 5%? Krugman certainly thinks so.

They began demanding austerity, and, as Krugman contends, “the political and media establishment internalized the preferences of the extremely wealthy.” At the start of the 2010s, the top 0.01% – 30,000 people around the world, half of them in the United States – cared little about high unemployment, which didn’t seem to affect them, but were greatly alarmed by government debt. Now, Nobel laureate economist Paul Krugman has offered an alternative explanation: plutocracy. Since then, the fact that the worst was avoided has served as an alibi for a suboptimal status quo. Each has argued that while enough was remembered to prevent the 1929-size shock of 2008 from producing another Great Depression, many lessons were plowed under by a rightward ideological shift in the years following the crisis. BERKELEY – Why did the policy response to the Great Recession only partly reflect the lessons learned from the Great Depression? Until recently, the smart money was on the answers given by the Financial Times commentator Martin Wolf and my Berkeley colleague Barry Eichengreen.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)